| Awazu Kiyoshi Poster for The Works of Kurokawa Kisho in 1970 |

The Metabolism

movement in architecture emerged Post-War in the late 1950's Japan, a country

that was recovering from the destruction of the war and entering a period of

economic growth. This group was influenced by the ideas of Team X, a group of

architects and designers who got together after the ninth Congress of CIAM

(International Congresses of Modern Architecture) and challenged the imposed

theoretical approach to urbanism at the time. In 1958, the CIAM disbanded

because of the split that was created. A

group of architects and a writer including Kenzo Tange, Takashi Asada, Kisho

Kurokawa, Kiyonori Kikutake, and Noboru Kawazoe started to plan the World

Design Conference of 1960 and met up to discuss the future of Japanese

architecture and urbanism. At the Conference in Japan, this group become known

as the ‘Metabolist’ group and presented their first pamphlet, Metabolism

1960: The proposals for a New Urbanism, including the works of Noboru Kawazoe, Kiyonori Kikutake, Fumihiko

Maki, Masato Otaka, Kisho Kurokawa, and Kiyoshi Awazu. This was their

first philosophical statement on architecture relating to a Buddhist notion of

impermanence and constant change and, therefore, abandoning all tradition

values of fixed forms and functions.

The name ‘Metabolism’ came from the experimental concept of living organisms that will reproduce, expand, and transform according to the environment as architecture. Their vision for cities of the future is of adaptable structures like the growth of organic matter for large-scale mass societies mainly concerning housing such as a marine city that can span over all of Tokyo Bay. The work of the Metabolists is often referred to as technocratic and is frequently compared to the conceptual work of the Archigram group including the Plug-in City, Living Pod, Walking City and Instant City. The Metabolist movement also influenced other architecture including Habitat ’67 by Moshe Safdie, Intrapolis by Walter Jonas, Space city by Yona Friedman, Swimming Hotel Kairo by Justus Dahinden, and Overbuilding the city of Ragnitz by Günther Domenig. One of the last works before the group separated was featured in the Osaka Expo in 1970.

The name ‘Metabolism’ came from the experimental concept of living organisms that will reproduce, expand, and transform according to the environment as architecture. Their vision for cities of the future is of adaptable structures like the growth of organic matter for large-scale mass societies mainly concerning housing such as a marine city that can span over all of Tokyo Bay. The work of the Metabolists is often referred to as technocratic and is frequently compared to the conceptual work of the Archigram group including the Plug-in City, Living Pod, Walking City and Instant City. The Metabolist movement also influenced other architecture including Habitat ’67 by Moshe Safdie, Intrapolis by Walter Jonas, Space city by Yona Friedman, Swimming Hotel Kairo by Justus Dahinden, and Overbuilding the city of Ragnitz by Günther Domenig. One of the last works before the group separated was featured in the Osaka Expo in 1970.

| ||

| Osaka Exposition 1970 |

|

| Expo Tower, Osaka 1970 by Kiyonori Kikutake (Constructed of a central steel pipe with geodesic sphere attachments allowing for further expansion and a panoramic view of the expo) |

|

| Beautilion Takara, Osaka Expo in 1970 by Kisho Kurokawa (a structure of cube caps giving an incomplete aesthetic as a concept of constant growth) |

| Marine City, 1958-1963 by Kiyonoiri Kikutake |

| Eco Polis by Kikutake Kiyonori, 1990 (Collage: Kikutake Kiyonori Digital retouch: Hagiwara Kei, 2011) |

| ECO POLIS by Kikutake Kiyonori (unbuild) early 1990s (Illustration: Morinaga Yoh) |

|

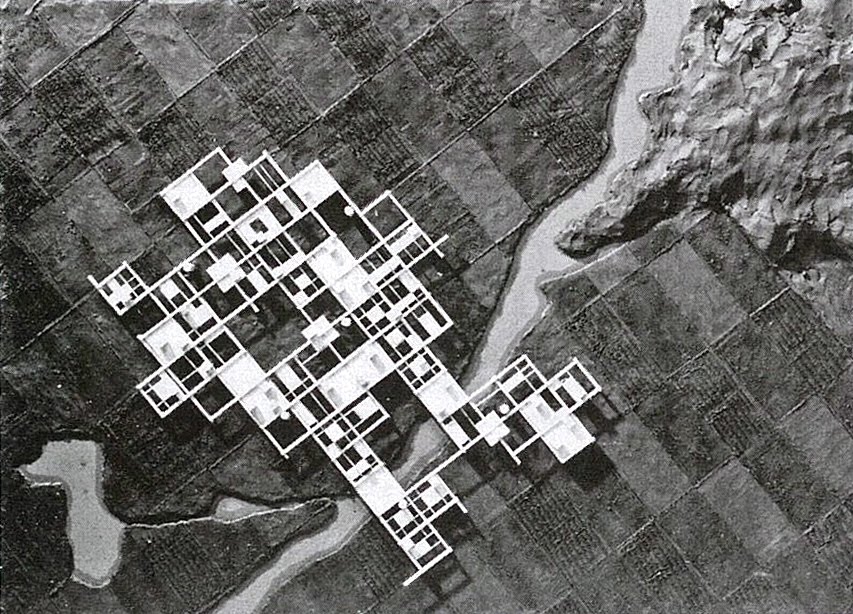

| Agricultural City Project by Kurokawa Kisho(unbuild),1960 (Illustration: Morinaga Yoh) |

| Syowa Station by Asada Takashi and others in 1957. Antarctic (Illustration: Morinaga Yoh) |

| Capsule Tower by Kisho Kurokawa (one of the most famous Metabolist residential and office building) |

| Nakagin Capsule Tower |